|

DAVE KYLE: |

In this issue, VG is proud to feature the first of a

series of stories commemorating the 25th anniversary of the

release of the first album by the Allman Brothers Band. This

month, we begin the tribute with the following historical

retrospective by VG contributor Dave Kyle, as well as

interviews with Joe Dan Petty, Allen Woody, and Jack Pearson. In

the next two months, we will continue the series with more

features and interviews with people close to the band.

Earlier this year, VG ran a piece on Gregg Allman.

Although not primarily known as a guitar player, Gregg is a fine

acoustic player, as anyone can attest if they've seen the

acoustic segment of an Allman Brothers Band show. While

researching the rest of the band, I mentioned to our editor,

Alan Greenwood, that Macon, Georgia, is a musically historical

place. Not just because of the ABB, but many other luminaries in

the music business have either lived or recorded in Macon.

"Why don't you get down there and talk to some of the people who

knew Duane," Alan said after one particularly long phone

conversation. "Maybe we'll do a sidebar on him."

Well, that project grew and grew, until it took on a life of its

own. Not only was I able to go to Macon and get some great

stories, I also went to Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where Duane

worked at the celebrated Fame Studios, playing on hits by people

like Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, Herbie Mann, Boz Scaggs

and a host of others. But I don't want to get too far ahead of

myself.

Let me give you a little background on Duane's all-too-short

life. There may be some statements included here and in previous

articles that seem to contradict each other, but time and

memories have a way of doing that.

Born in Nashville, Tennessee in 1946, Duane was very young when

he lost his father, a military man, to a senseless murder at the

hands of a hitchhiker. Before moving to Daytona Beach, Florida,

Geraldine Allman enrolled Duane and Gregg in Castle Heights

Military Academy, Lebanon, Tennessee.

The boys and their mother, "Mama A" as she is known to their

many friends and family, then moved to sunny Daytona, Florida in

1959, where Duane and Gregg attended Seabreeze High School. As

Gregg said in his interview (VG, July '96), he was

visiting his grandmother in Nashville one summer, when he picked

up some guitar chords from one of her neighbors, Jimmy Baine.

Duane checked out the guitar his little brother bought at Sears

and to quote Gregg, "...he passed me up in about two weeks. He

was a natural."

Gregg says this with the conviction of one who knows, having

been around many of the greatest guitar players of our time.

After countless fights over the low-cost acoustic, Mama A

decided to get each boy a guitar. Gregg got a Fender Musicmaster

and Duane got a Gibson Les Paul Jr., which is now reportedly

owned by Delaney Bramlett.

A succession of bands followed, including Escorts, Almanac, the

Allman Joys, the Untils (with present day Gregg Allman and

Friends sideman Floyd Myles) and Hourglass. The brothers began

their career playing "beach music," a natural progression for a

Florida band in the ‘60s. Gregg soon got in to the blues, thanks

to Floyd, and again, brother Duane followed. He traded a wrecked

motorcycle for a guitar and the rest, as they say, is history.

"One year, Gregg got a guitar for Christmas and I got me a

Harley 165 motorcycle. I tore that up and he learned to play,"

Duane said in an early-’60s interview by Tony Glover. "He taught

me and I traded the wrecked bike parts for another guitar."

The Allman Joys became one of Florida’s best-known bands. After

changing their name to the Hourglass, they signed a record deal

which led to an ill-fated trip to California. They spent a short

time in Los Angeles making two albums for Liberty, until Duane

became fed up with the scene and decided to move, "...back down

South where I belong," according to Gregg, who stayed in

California to fulfill contractual agreements.

The record company insisted on dictating material the band would

record. Again, according to Duane, "...they’d send in a box of

demos and say, 'Okay, pick your next LP.' We’d try to tell them

that wasn’t where it was at. Then they’d get tough."

Duane then moved to Muscle Shoals and started his career as one

of the late ‘60s most noted studio guitarists.

It was Duane's idea for Wilson Pickett to cover the Beatles'

"Hey Jude." He wasn’t taken seriously

at first, an reportedly called Pickett "chicken" to try

something out of the ordinary. This, of course, prompted Pickett

to do the song.

Duane laid down a deep groove, and the song re-wrote itself.

That, along with the slide work on Aretha Franklin's cover of

the Band's "The Weight" propelled Duane into a category of

guitar greats. For the first time to anyone's knowledge, outside

of people like Chet Atkins and Duane Eddy, a guitar player who

couldn't really sing was offered a recording contract.

Rick Hall, proprietor of the well known Fame Studios, in Muscle

Shoals, heard him play on a demo recorded by Johnnie Johnson,

another stalwart guitarist, and signed him, later selling his

contract to Atlantic Records. This was unheard of at a time when

psychedelic music was becoming the vogue. Phil Waldon, who had

booked the likes of Otis

Redding and

many other great R and B act's of the day,

heard him play and bought the contract from Atlantic.

Not really knowing what to do with what they had, a recording

project was started with Duane as an artist. Duane had a vision

of the kind of band he wanted to create, but he wasn't able to

tell the powers that be what that was. The project., which was

scrapped but eventually saw release as the posthumous Duane

Allman, An Anthology turned into what we know today as the

Allman Brothers Band. Duane rounded up several musicians he had

worked with in the past, including Jai Johnny (Jaimo) Johnson.

He and Duane paired up and hit the Muscle Shoals scene like a

June tornado. They were a legendary jamming team that knocked

out the musicians there. Not an easy feat, considering they’ve

played with the who’s who of music for several decades. Going

back and forth between Jacksonville and Muscle Shoals, where he

continued to record, Duane eventually found the other members of

his dream group. Claud Hudson "Butch" Trucks, a native of

Jacksonville, became the other half of the drumming duo. Gregg

recalled meeting Butch in Daytona "out on the street, with all

this equipment, "where he

and his band,

the 31st of February, had just been fired.

One person Duane’s heart was set on was Berry Oakley, originally

from Chicago, Illinois. Berry had played guitar with Tommy Roe

and the Roemans and was now playing bass in a band with his

friend Dickey Betts on guitar. Dickey was another Florida guy,

born in West Palm Beach. The two were inseparable at the time

and Berry would not leave his friend's band. Duane had not

originally planned on having two guitar players n the band, but

Berry's fierce loyalty led him to decide that if he had to take

Dickey to get Berry, so be it. That decision made for one of the

most unique sounds of the day, with twin guitars played in

harmony as they had never been before. Reese Wynans (later part

of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Double Trouble) played Hammond

B-3 with the band until Duane convinced Gregg to come back to

Florida. Gregg showed apprehension at the lineup, but being

homesick and frustrated with the L. A. music scene, he jumped at

the chance. It has been reported many times that when the band

was finally assembled and sat down to jam in the Green House,

magic happened. Hours after the first song had started, Duane

supposedly made a move for the door.

"Anyone who doesn’t want to join my band has to fight his way

out!" he said.

Phil Waldon started Capricorn Records and Capricorn Studio in

Macon, and the band moved, enmassé, to southcentral

Georgia, which in the late ‘60s was not accustomed to seeing a

band of five longhaired hippie types and a black guy move in

together. They found a large house at 309 College street, where

a month after they moved in, everybody else moved out. The place

became known as the Hippie Crash Pad. The band lived well below

the poverty level, surviving primarily on VA checks and a small

salary provided by Twiggs Lyndon, their future road manager, and

whatever else they could scrounge up.

At a local meat and three (vegetables, for you non-Southern

types) restaurant called the H & H Diner, a matronly black lady,

know affectionately to the band as "Mama Louise" (Hudson, one of

the Hs) took pity on the poor musicians and fed them even when

they didn’t have money. The band would rehearse a while each

day, grab a bite at the H & H, rehearse some more and party all

night. After a late-morning wake up, they’d do it again. If

you’re interested, the H & H is still open and serves a great

meal. I highly recommend it.

One of their favorite spots to party was the beautiful Rose Hill

Cemetery in Macon. There, straight through the main gate and

along the river, is the burial site of one Elizabeth Reed

Napier, who was immortalized in Dickey Betts' beautiful tune,

"In Memory of Elizabeth Reed."

As the band got tighter and tighter, doing covers of old blues

songs by people like Muddy Waters and adding Gregg’s originals,

they started playing road dates, traveling in very humble

conditions, as did most of the bands of the time. Each weekend,

they set out for parts unknown, crisscrossing the country,

making friends and fans wherever they went..

One of the venues was Bill Graham's Fillmore clubs (East and

West). Graham loved the band and would help them fill out their

schedule when they needed more dates. In the meantime, two

albums emerged, The Allman Brothers Band and Idlewild

South, which was

named after a farmhouse outside Macon

where the band and friends partied. Each album sold

respectively, but no big hits were forthcoming.

The tours continued and a Winnebago finally replaced the van,

much to

everyone’s delight. In 1971, they recorded

several live shows at Graham’s Fillmore East in New York, which

later became The Allman Brothers, Live at the Fillmore East.

This double album probably seemed like a risk at the time,

but as any true ABB fan will tell you, you haven’t really

experienced the band until you’ve heard them live. This album

captured that feel like none before, and was probably their

biggest breakthrough. In this time of album rock radio stations,

it looked like they were finally catching on with the public and

getting their well-deserved recognition.

At about that time, the band was doing a show in Florida when

their producer, Tom Dowd, said

Eric

Clapton was recording at Miami’s Criteria Studio. Duane asked if

it was possible to meet him. Dowd said he would see what he

could do.

When he heard, Clapton said he was a fan of Duane’s since

Pickett’s "Hey Jude" record. He and Dowd attended an outdoor gig

the band was playing. The place was packed, so they crawled

under the stage and sat down in front between the audience and

the band. When Duane saw Clapton staring up at him, he froze in

midsolo. The band covered for him and looked to see what had

caught his attention so abruptly. They were all a little nervous

at the prospect of having one of the world’s most well-known

guitarists sitting front and center, but they continued the

concert, then met Clapton after the show.

This "mutual admiration society" led to one of the most

acclaimed albums of all time, Clapton's Layla and Other

Assorted Love Songs. The two monster players collaborated on

the album's title song and several others. Although Duane did

not play on the entire album, due in part to the Allman

Brothers' touring schedule, he was responsible for the signature

lick on "Layla," which nearly every budding guitar player has

studied.

The two styles melded into one huge guitar sound that was

sometimes confusing for the uneducated listener Ever the

guitar-oriented guy, Duane tried to explain it by telling people

"...I played the Gibson and he played the Fender." Guitarheads

understood, but the general listening public was still unsure,

and unfortunately, many still don't realize that one of the most

recognizable licks ever was Duane Allman's. Most agree

that this was a high point, if not the high point for

both of these world-class talents.

Duane, Gregg and Berry had moved into what came to be known as

the Big House, a large, old Southern mansion at 2321 Vineville

Avenue in Macon. They and their wives, girlfriends and children

lived there eating large family-style dinners in the huge dining

room, and rehearsing in the front two rooms, generally living as

one big family. Dickey and his wife lived not far away and he

would spend time there when Duane and Gregg were having

difficulty. Dickey wrote "Ramblin' Man" in the kitchen and "Blue

Sky" in the living room of the Big House.

At some point, Duane and

his common law (according to Georgia

statutes) wife, Donna, moved to an apartment on Bond Street,

just a block or two from the original Hippie Crash Pad on

College. Gregg moved to an apartment with his wife, Shelley, at

839A Orange Terrace, overlooking downtown Macon, just a block

away from the Medical Center of Central Georgia, the hospital

that would play a vital role in the band's near future.

After the success of Fillmore East the band decided

to stay off the road for awhile and

relax in Macon while working on their new album Eat A Peach.

The title came from a comment Duane made to an interviewer

who asked the question "...what are you doing for the

revolution?"

"There ain't no revolution, just evolution," Duane reportedly

said. "When we come back to Georgia we eat a peach for peace.

That's what we're doing."

Most of the songs were cut for the new album and the relaxation

was beginning to relieve the pressures of road life. Berry's

wife, Linda, was having a surprise birthday party on the 29th of

October and Duane drove his motorcycle to the Big House to

attend. The band was going to get together that evening for a

jam session, so Duane left for home.

On the way, at the intersection of

Hillcrest and Bartlett, his motorcycle collided

with a flatbed truck. His girlfriend,

Dixie (Duane and Donna had since gotten

a divorce) and Candace Oakley, Berry's

sister, were behind him and witnessed the accident. His Harley Davidson Sportster

crashed down

on his chest, crushing him. Although he

reportedly looked okay at the scene, he was not conscious.

He was rushed into surgery at the hospital. When Gregg got the

news, he ran down the street to be with Duane, who died three

hours later, at 8:40 p.m. He was 24 years old, and his death

left a gap in the leadership of the Macon musical community and

beyond.

Disbelief is a word often used when talking to those who were a

part of that community. This young, talented spark had ignited

the band to levels none dreamed possible. But life goes on.

The funeral was attended by several musical luminaries who,

along with the Allman Brothers Band, performed at the service.

Dr. John, who had toured with the band and lived in Macon, and

Delaney Bramlett, who had hired both Duane and Clapton as guitar

players for his band, were among these performers.

Duane’s beloved ‘59 Les Paul was placed in front of the

floral-wreathed casket. This proved foreboding. For people like

myself, who naturally supposed that the group was finished, it

held a hope that this supergroup Brother Duane had assembled

would somehow carry on.

And carry on they did.

The album in progress was finished, with some already-recorded

material as well as tracks leftover from the Fillmore

album. Tom Dowd, who had produced that album, and was producing

Eat A Peach, had other commitments which he had to see to

after the delay. So Johnny Sandlin, an old friend of Duane’s,

who then worked for Capricorn, was called in to finish the

project.

Betts was put in the unenviable position of being compared to

his predecessor. Though their styles were similar, just as

Duane’s had been with Clapton, Dickey had his own thing going

on. He stepped up to the plate and knocked the hide off the ball

with songs he had written and sang, giving the band a new focus.

Deciding not to try to replace the irreplaceable, they finally

chose pianist Chuck Leavel (currently the keyboard player with

the Rolling Stones) as a fresh addition. His playing propelled

the band to new and different heights and they kept on doing

what they do, making great blues-based rock and roll.

On November 11 the following year, irony took another stab at

the band. Bassist Berry Oakley, who had more or less taken the

reigns Duane had held, was taken from us in yet another cruel

twist of fate. While riding motorcycles with friend and roadie

Kim Payne, Berry missed a curve near the intersection of Napier

and Inverness, just blocks from the site of Duane’s fatal crash,

and hit a Macon city bus.

This blow was almost unbelievable to anyone who was vaguely

familiar with the band’s history. Although unconscious at first,

he came to and took a ride home with a passing motorist,

refusing to go to the hospital. Later

that afternoon, he was taken to the same emergency room, talking

incoherently, and he later died. Like Duane, Oakley was 24 years

old when he died.

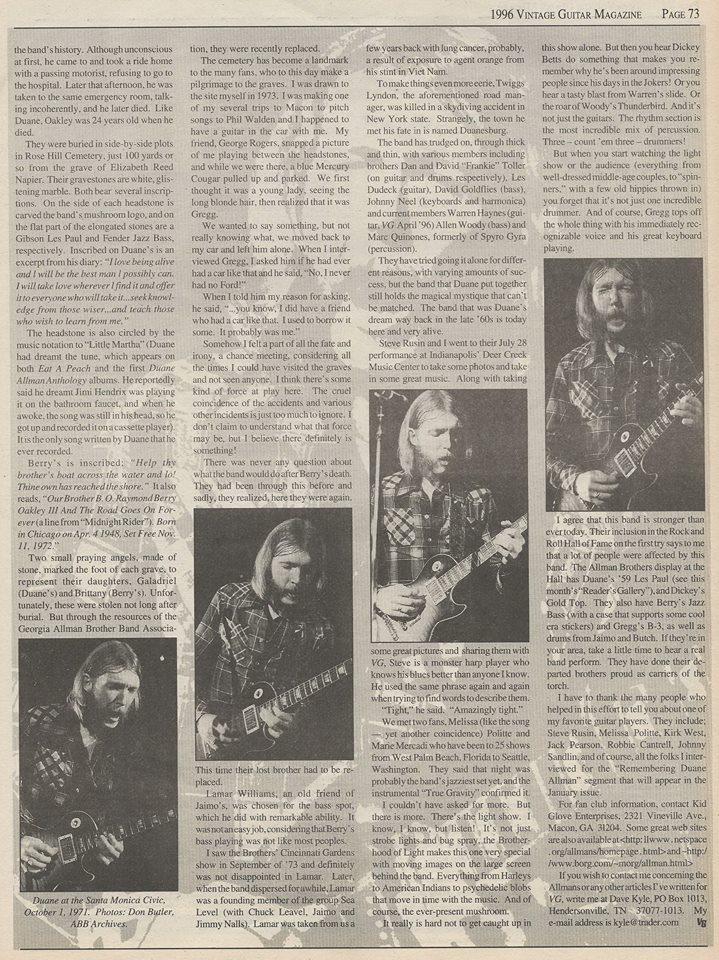

They were buried in side-by-side plots in Rose Hill Cemetery,

just 100

yards or so from the grave of Elizabeth Reed Napier. Their

gravestones are white, glistening marble. Both bear several

inscriptions. 0n the side of each

headstone is carved the band's mushroom logo, and on

the flat part of the elongated stones are a

Gibson Les Paul and Fender Jazz Bass,

respectively. Inscribed on Duane's is

an excerpt from his diary: "I love being alive and I will be

the best man I possibly can. I will take love wherever l find it

and offer it to everyone who will take it...seek knowledge from

those wiser...and teach those who wish to learn from me."

The headstone is also circled by the music notation to

"Little Martha (Duane had dreamt the

tune which appear on both Eat A Peach and the first

Duane Allman Anthology albums. He reportedly said he dreamt

Jimi Hendrix was playing it on the bathroom faucet, and when he

awoke, the song was still in his head, so he got up and recorded

it on a cassette player). It is the only song written by Duane

that he ever recorded.

Berry’s is inscribed. "Help thy

brother's boat across the water and lo! Thine own has reached

the shore." It also reads, "Our Brother B 0. Raymond

Berry Oakiey III And The Road

Goes On Forever (a line from "Midnight Rider"). Born in

Chicago on Apr. 4, 1948, Set Free Nov. 11, 1972."

Two small praying angels, made of stone, marked the foot

of each grave, to represent their daughters, Galadriel (Duane's)

and Brittany (Berry's). Unfortunately, these were stolen not

long after burial. But through the resources of the Georgia

Allman Brothers Band Association, they were recently replaced.

The cemetery has become a landmark to

the many fans, who to this day make a pilgrimage to the graves.

I was drawn to the site myself in 1973. I was making one of my

several trips to Macon to pitch songs to Phil Walden and I

happened to have a guitar in the car with me. My friend George

Rogers, snapped a picture of me playing between the

headstones, and while we were there, a blue Mercury Cougar

pulled up and parked. We first thought it was a young lady,

seeing the long blonde hair, then realized that it was Gregg.

We wanted to say something, but not

really knowing what, we moved back to my car and left him alone.

When I interviewed Gregg, I asked him if he had ever had a car

like that and he said, "No, I never had no Ford!"

When I told him my reason for asking, he said, "...you know, I

did have a friend who had a car like that. I used to borrow it

some. It probably was me."

Somehow I felt a part of all the fate and

irony, a chance meeting, considering all the

times I could have visited the graves and not seen anyone. I

think there's some kind of force at play here. The cruel

coincidence of the accidents and various other incidents is just

too much to ignore. I don’t claim to understand what that force

may be, but I believe there definitely is something!

There was never any question about what the band would do after

Berry's death. They had been through this before and sadly, they

realized, here they were again. This time their lost brother had

to be replaced.

Lamar Williams, an old friend of Jaimo's, was chosen for the

bass spot, which he did with remarkable ability. It was not an

easy job, considering that Berry's bass playing was not like

most peoples.

I saw the Brothers' Cincinnati Gardens show in September of '73

and definitely was not disappointed in Lamar. Later, when the

band dispersed for awhile, Lamar was a founding member of the

group Sea Level (with Chuck Leavel, Jaimo and Jimmy Nalls).

Lamar was taken from us a few years back with lung cancer,

probably, a result of exposure to agent orange from his stint in

Viet Nam.

To make things even more eerie, Twiggs Lyndon, the

aforementioned road manager, was killed in a skydiving accident

in New York state. Strangely, the town he met his fate in is

named Duanesburg.

The band has trudged on, through thick and thin, with various

members including brothers Dan and David "Frankie" Toller (on

guitar and drums respectively), Les Dudek (guitar), David

Goldflies (bass), Johnny Neel (keyboards and harmonica) and

current members Warren Haynes (guitar, VG April '96)

Allen Woody (bass) and Marc Quinones, formerly of Spyro Gyra

(percussion).

They have tried going it alone for different reasons, with

varying amounts of success, but the band that Duane put together

still holds the magical mystique that can't be matched. The band

that was Duane's dream way back in the late '60s is today here

and very alive.

Steve Rusin and I went to their July 28 performance at

Indianapolis' Deer Creek Music Center to take some photos and

take in some great music. Along with taking some great pictures

and sharing them with VG, Steve is a monster harp player

who knows his blues better than anyone I know. He used the same

phrase again and again when trying to find words to describe

them.

"Tight," he said. "Amazingly tight."

We met two fans, Melissa (like the song - yet another

coincidence) Politte and Marie Mercadi who have been to 25 shows

from West Palm Beach, Florida to Seattle, Washington. They said

that night was probably the band's jazziest set yet, and the

instrumental "True Gravity" confirmed it.

I couldn't have asked for more. But there is more. There's a

light show. I know, I know, but listen! It's not just strobe

lights and bug spray, the Brotherhood of Light makes this one

very special with moving images on the large screen behind the

band. Everything from Harleys to American Indians to psychedelic

blobs that move in time with the music. And of course, the

ever-present mushroom.

It really is hard not to get caught up in this show alone. But

then you hear Dickey Betts do something that makes you remember

why he's been around impressing people since his days in the

Jokers! Or you hear a tasty blast from Warren's slide. Or the

roar of Woody's Thunderbird. And it's not just the guitars. The

rhythm section is the most incredible mix of percussion.

Three - count 'em three - drummers!

But when you start watching the light show or the audience

(everything from well-dressed middle-age couples, to "spinners,"

with a few old hippies thrown in) you forget that it's not just

one incredible drummer. And of course, Gregg tops off the whole

thing with his immediately recognizable voice and his great

keyboard playing.

I agree that this band is stronger than ever today. Their

inclusion in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on the first try

says to me that a lot of people were affected by this band. The

Allman Brothers display at the Hall has Duane's '59 Les Paul

(see this month's "Reader's Gallery"), and Dickey's Gold Top.

They also have Berry's Jazz Bass (with a case that supports some

cool era stickers) and Gregg's B-3, as well as drums from Jaimo

and Butch. If they're are in your area, take a little time to

hear a real band perform. They have done their departed brothers

proud as carriers of the torch.

I have to thank the many people who helped in this effort to

tell you about one of my favorite guitar players. They include:

Steve Rusin, Melissa Politte, Kirk West, Jack Pearson, Robbie

Cantrell, Johnny Sandlin, and of course, all the folks I

interviewed for the "Remembering Duane Allman" segment that will

appear in the January issue.