Bomb scares,

telepathic jams and one unforgettable

all-night gig

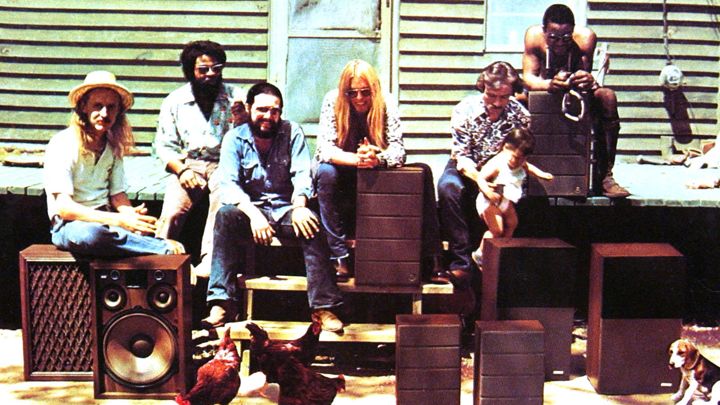

The Allman Brothers in

1970, the year before they recorded 'At

Fillmore East' (GAB Archive/Getty)

Forty-five years ago, on March 11th,

1971, the Allman Brothers Band took the

stage at Bill Graham's vaunted Fillmore

East Theater in New York for the first

of a series of shows that are among the

most celebrated in rock history. The

Allmans weren't even supposed to be the

headliners. The posters Graham had

printed up read: "Johnny Winter and

Elvin Bishop Group. Extra Added

Attraction: Allman Brothers." By the end

of the first night, the order had been

forcibly flipped on its head.

During six sets of music spread across

three evenings, the Allman Brothers Band

— undeterred by bomb threats and a

disastrous experiment with a patchwork

horn section — pushed their songs to

their very limits and redefined what it

meant to jam onstage. The nearly

23-minute version of "Whipping Post"

that closed the final night on March

13th set a high water mark in the

then-fledgling tradition of Southern

rock.

Three months later, on June 27th, the

Brothers were back at the Fillmore East

once again but under completely

different circumstances. The venue was

closing its doors forever and perhaps

remembering the magic of their last run

on his stage, Graham had handpicked the

Allman Brothers Band to give his beloved

concert hall a final, proper sendoff.

They played until dawn, and when the

show was over, a great church of rock,

soul, jazz and blues music went along

with it. Three months after that, Duane

Allman — half of the '71 group's iconic

guitar tandem — died in a Georgia

motorcycle accident.

Rolling Stone recently caught up

with some of the people onstage at that

legendary run to discuss how those shows

came together, and why they've endured

in the minds and hearts of so many rock

fans for nearly five decades.

Gregg Allman, Allman Brothers Band

singer/keyboardist: Bill Graham was

the most assertive person I've ever met.

He was a straight shooter, a no-bullshit

kind of guy. You always knew where you

stood with Bill, man. He pulled no

punches, but as tough as he was, he was

always very fair.

Butch Trucks, Allman Brothers Band

drummer: You just didn't want to get

in his way. Bill Graham did not tolerate

people doing a half-assed job, and it's

the reason that playing the Fillmore and

being in the audience at the Fillmore

was so great. He ran it like clockwork,

and he made sure that everybody in every

seat could see and hear correctly.

Dickey Betts, Allman Brothers Band

guitarist: He was a great guy. You

know, either you hated Bill or you loved

him, and I was one of the latter. He was

one of the cornerstones of getting our

band going.

Elvin Bishop, Elvin Bishop Band

singer/guitarist: He ran a good

organization both on the West Coast and

the East Coast. He was kind of

revolutionary because, before he came

along, concerts were all one kind of

music. They would never mix things up,

and Bill Graham would have Rahsaan

Roland Kirk, Albert King and the

Jefferson Airplane all on one show.

Trucks: When I met Bill Graham

for the first time, it was when I showed

up for that closing night and walked

across the stage. [He] saw me and came

running. Up until that time I had never

met him. He was always just this voice

you heard on the other side of the room

chewing somebody's ass out who screwed

up the night before. Anyway, he came

running across the stage and grabbed me

by the neck, and he was a large, strong

man and he said, "I can't thank you

enough for last night." And he went on

and on and on, but in a nutshell he

said, "It makes all the years of

bullshit that I've had to put up with

worthwhile."

Allman: The Fillmore was

originally an old Yiddish theatre built

back in the Twenties, and it had a great

vibe to it, man. The acoustics were

nearly perfect in there. It had nice

sight lines for the fans, and I think it

held about 2,000 people or so, which was

just right. The Fillmore East became a

regular stop for us. It was like we had

almost become the house band or

something.

Betts: It was a great-sounding

room. It was fun to play. Then you had a

guy like Bill Graham that made sure that

the PA system was set up correctly. It

wasn't too loud, it wasn't too soft, and

everyone in the room could hear and see.

Trucks: The audience was great

and the sound was great. Every time you

went in there it just sounded so goddamn

good, and the audiences were just so in

tune with what's going on.

Allman: Bill wouldn't pay you as

much as some other promoters, but Bill

would take a chance on people, and if

you were good enough, he'd invite you

back time and again, so we never worried

about what he paid us.

Rock promoter Bill Graham onstage at

the Fillmore East. (John Olson/Getty)

Betts: [He] presented the show in

a very sophisticated way, in a way that

many people weren't used to seeing a

rock & roll show done. He took a lot of

cues from Broadway, I guess, like

rolling drum sets on risers and rollers

and setting them up on the sides. He

could change bands very quickly. He had

his light show, and it was very

state-of-the-art back then, and he would

get the old urban and Delta-blues

players and educate the audience to what

they meant to rock & roll.

Allman: My brother had always

believed a live album was what the

Brothers needed to do, and the record

company finally agreed with him. The

Fillmore was just the logical choice. I

don't think we even discussed another

venue.

Trucks: That was one of the first

places that the audience really got it.

You know why we were able to record

At Fillmore East? We actually

weren't the headline that weekend. You

go back and look; we were the special

guests for Johnny Winter. But after we

played our first set on Thursday night,

half the audience got up and walked out.

Steve Paul, who was Johnny Winter's

manager, said, "Well, I guess Johnny is

gonna be opening for the Allman Brothers

from now on because we can't have that

happen again." If that hadn't happened,

we absolutely wouldn't have had all that

time to do all the stretching out that

led to At Fillmore East. We only

had 90 minutes and had some songs that

lasted longer than that!

Betts: It became obvious that we

were a great band live. We could really

play and the record people came up with

the idea that, "Man, these guys need to

be caught in the act." We had a great

situation. You know, we had [producer]

Tom Dowd and Johnny Sandlin that came in

and [recorded] those shows and they did

a great job of it of course.

Trucks: We learned very early on

that playing music is a very selfish

thing. We're up there playing for

ourselves first and foremost. If I'm not

getting myself off, how can I expect

anyone else to get off on it? I start

with myself then move out to the guys in

the band, and then we start

communicating. We kick it into overdrive

and go into places that we can't go by

ourselves.

Allman: We just played and

played, one gig after another. You got

to remember that we spent 300 days on

the road in 1970. I mean, we were never

home. All we did was play, man.

Trucks: If it wasn't for Tom Dowd

and his genius at knowing acoustics and

setting up microphones ... There were

certain things that he did to get the

sound that you just can't miss on At

Fillmore East that every engineer

out there would scream and holler is

completely heretical. For one thing, Tom

Dowd always told us that the most

important thing about making a live

album is that the most important

microphones on that stage are pointed at

the audience. He wanted all the sound on

the record to feel like what it was like

if you were at the Fillmore East, so he

opened all of the vocal mics onstage and

left them open for the whole show. Not

once did he shut anything off. He knew

that we could play well enough and that

as long as we were playing our best,

[the album] was not going to have to be

remixed or repaired or anything else.

You get all that ambience coming at you,

and you don't have to add a whole lot of

outboard equipment or reverb or this,

that and the other.

Allman: Tom almost missed

recording the album. He'd been on

vacation in Europe, and he only flew

back to New York because the weather had

been shitty in France or wherever. Tom

didn't even know we were recording that

night, and when he found out, he barely

made it into the truck. Thank God he

did, or who knows what might have

happened.

Betts: He was a great guy to work

with and he was so subtle with his

psychology. It took a while for me to

figure out how good he was. I thought he

didn't do anything! He would be there

without seeming like he was intruding.

There was one thing that I finally

figured out that he was doing. If I was

trying to do a guitar solo, he would

say, "You know, that was good, but I

really like what you were doing back

when we first started tonight." And I'd

say, "What's that?" And he would sing to

it and say, "Well you started out with

this." Then I finally realized that I

had never done that [laughs]. It

was his idea, but he didn't want to seem

like he was telling me what to play. I

loved him for that.

Betts: There was kind of a

running joke in the music business.

Nobody said it in public in an interview

or anything, but people would say, "The

only thing live on such-and-such record

was the audience." [Laughs.] And

I'm not saying anything bad about any of

the other bands that we worked with and

stuff, but a lot of times they would go

back into the studio and re-do things;

re-do vocals and stuff. The Fillmore

East album is absolutely live. We

didn't go back and re-record one guitar

solo; we didn't add anything to it. Now

there is some editing because we had

some horn players and some harp solos

that ran about three times longer than

they should have been.

Trucks: We did some vocal

overdubs, but everything else is just

what we played.

Allman: The mood was good. It was

always good, man, so the only change was

we left the horn players out on the

second night, except for Juicy Carter,

and he only played on a few songs.

Trucks: There were three guys who

used to play with Jaimoe out of

Mississippi: Juicy, Fat and Tick. Juicy

was the baritone player, and he used to

play with us a lot — for years and

years. Fat played the alto, and of the

three of them, he was probably the only

one that could really play. And Tick

played tenor. You put all three of them

together with us playing at the level we

were playing, and they just weren't

there. After the opening night when we

finished, Tom said, "Nix the horns! No

way! That sucked! No fucking way!" Duane

looked at him like, "Huh? I thought this

was our band." Luckily Duane trusted

Tom's judgment enough to say, "OK."

Duane was just of the mind that you

gotta include the whole world in what

we're doing. He was constantly looking

for ways to expand what we were doing.

Allman: My brother liked having

them sit in from time to time, so to us,

it was no big deal.

Betts: Duane was a very, very

wise man for 22, 23 years old. It was

really easy to talk sense with him about

what we were trying to do. Let's say we

were riding from Georgia down to Florida

where our folks lived and stuff, and

we'd be drinking a little bit and having

these long conversations about things

like the Zen aspect of it all. Finding

that innocence of mind, or what athletes

call "getting in the zone." You just get

free and let things happen rather than

make things happen. We used to laugh

about so many bands who busted up

because the guitar players would get so

jealous and try to outdo each other all

the time. We had an understanding that

that was the worst thing you could do.

It's not a contact sport. It's music.

Bishop: I thought they were

great. I liked how they just went for

it. I kind of agreed with their concept

of giving it enough structure so that

the bottom never fell out, but enough

freedom that you could jam good.

Allman: My brother, he was the

bandleader on stage. He'd count it off

to start a song, and we would end it

when he raised his hand, but in between,

the band just let itself go wherever the

music would take us.

Trucks: For my entire career,

from the moment Duane Allman reached

inside me, flicked the switch and turned

me on, to this day, I've always locked

on whoever is playing lead, whether it

was Duane, if it was Dickey, if it was

Gregg or if it was Barry Oakley. Quite

often, I will see something they're

doing, even if I can't hear it. I'm so

comfortable in just feeling Jaimoe that

I don't have to listen to 'em. He's just

there. So if someone plays a lick or

goes somewhere, I'm right on their ass,

and it's my job to stay on their ass and

push them to higher places. I think it's

how I got the name "The Freight Train."

Betts: It would switch from one

guy to the other as the song evolved. We

didn't have anybody we took cues from.

We just followed each other. [Barry]

Oakley was great if a song was starting

to lag. He would start really pumping on

the bass to pull us into another

direction. At the same time, I would do

that too, start a riff or something that

would kind of pick it up and make it

sound good in a certain situation. Duane

did the same thing.

Allman: My brother made up the

set list, and it didn't change very much

from night to night. He liked it that

way. We'd swap out a song or two, but we

pretty much kept the same songs. The

thing was, we'd never play them the same

way twice.

Trucks: I seem to remember us

going out there to the recording truck

and listening to the set we just played

and then we'd work out what we'd do

next.

Betts: We just played whatever

came up. Somebody would say, "Let's play

'One Way Out' or something." Well,

except for "Whipping Post," which we

usually saved for the end of the show

because it was such a slammer. "In

Memory of Elizabeth Reed," we'd put that

near the end of the show.

Trucks: In those days, when we

climbed into those songs, that's all

there was. It's never been like that

since. I mean, I've been able to get

into the moment for brief times many,

many times since then, but not for those

long extended jams like on "Whipping

Post," for instance, where once the song

started, you climbed in and there was no

tomorrow, no yesterday; you were just

totally in the moment from the time it

started to the time it ended. On every

song on that album, that's what was

happening. We were just at the peak of

reaching the point where we knew each

other well enough, we knew the material

well enough to where we didn't have to

think about it and could let it all flow

so naturally. We knew what each other

was going to do — yet we were constantly

wide open to letting it go and taking a

dive and seeing what would happen.

Allman: ["Whipping Post"] was

intense, man! Like I said, that whole

set was intense.

Trucks: When you listen to

Dickey's solo on "Whipping Post," he

just lets everything go. We're just

doodling around, letting him go, and

then all of a sudden, he starts playing

this melody [sings], and you can hear

Barry and Gregg and Duane all feeling

around for where this chord progression

is because we'd never done this before.

By about the second or third progression

through, Barry and Duane had locked in

to what the chord progression was and

then Dickey really laid into it and it

just fucking took off. Then when we came

roaring back in with the "Whipping Post"

theme again, the place just exploded. We

had just paid a visit to a place we'd

never been before.

A set list from the Allman Brothers

Band's famous 1971 performance at the

Fillmore East. (Dorie Turner/AP)

Allman: A bomb scare made that

night's second set start real, real

late, and boy, did we get into a serious

groove. We played some mind-blowing

stuff in that set.

Bishop: I think there had been a

bomb scare or something that happened.

We were all gone for a couple of hours

out of there, and when we came back, I

guess they ran out of tunes so they got

me to come up and jam on "Drunken

Hearted Boy."

Trucks: There were several [bomb

scares] right around the same time. I do

remember one at the Fillmore the weekend

we were recording. Apparently they did

find something. I never found out

whether it was a bomb or not; they just

said that they found something in one of

the balconies. I have a feeling that

there wasn't a bomb, but rather than

just saying, "We just wasted your time

and emptied all of these buildings for

nothing," we'll just tell you we found

something. I just remember standing

outside for a very long time thinking,

"Hey, we should be inside playing

music." And, "All these people were in

such a great state of mind and now we're

gonna have to go back to work to get

them back into that frame of mind again,

as well as ourselves."

Trucks: The cover was supposed to

obviously look like the outside of the

Fillmore East where you supposedly load

in and out, but that's actually in an

alleyway across the street from

Capricorn Records on Broadway in Macon,

Georgia. Our roadies just took our

equipment truck out and line-loaded all

our gear and packed it up and then

somebody stenciled The Allman

Brothers at Fillmore East on one of

the cases.

Betts: Jim Marshall wanted us to

be there at daylight in this alleyway to

shoot these pictures and we thought,

"Now what the fuck do we need to be out

there at daylight for?" He wanted that

natural yellow light, you know? He

didn't want to use flashbulbs or have a

bright sun banging away at the situation.

So anyway, we stayed up all night and

went down there.

Trucks: We all sat down, and Jim

Marshall had set himself up in the truck

so he could get high enough to get the

right perspective for the pictures. Then

he started hollering at us about who to

be where and do this now, do that now. I

mean, he was not at all nice. He was a

real son of a bitch who was lucky he

didn't get his ass kicked. At one point,

some guy walked up to the side of the

truck and right in the middle of taking

all the pictures, Duane just jumps up

and takes off to the side of the truck.

Marshall goes ballistic, but we all saw

what he was doing — he was picking up an

eight ball from his connection. So he

ran back, sat down real quick, Marshall

is going, "Blah, blah!" and we all just

busted up laughing. Luckily, he had

enough sense in his tirade to take a

picture, because that's the picture, and

it's the only one of the whole goddamn

day when we weren't snarling at him like

a bunch of pitbulls.

Allman: At Fillmore East

went gold on October 25th, 1971. Four

days later my brother was dead.

Trucks: [The record company] did

not want to put it out. They fought with

us and fought with us and fought with

us, until they finally realized if they

were gonna have anything at all, then

that's what they were gonna have. We

were firmly convinced that we would

never be a big-money band because

Atlantic Records had pounded that into

our heads. "You're a Southern band, and

you're playing music, especially with a

black guy in the group ..." This is

exactly what we heard from Jerry Wexler.

"You gotta get Gregg out from behind

that keyboard, stick a salami down his

pants, and make him jump around onstage

like Robert Plant, then maybe you got a

chance." Basically we just said, "Fuck

you!" We had tried that kind of shit

before and not only did we hate it, we

hadn't made a plug fucking nickel, much

less become big rock stars. We decided

that the music we were playing was much

more important than becoming rock stars.

Fillmore East before its closing.

(New York Daily News Archive/Getty)

Allman: It meant so much to us

that Bill Graham wanted the Brothers to

close it all out at the Fillmore.

Betts: That was a special show.

We played until daylight that morning. I

remember it was dark in there, and when

they opened the door, the sun about

knocked us down. We didn't realize we

had played until seven, eight o'clock in

the morning. Bill Graham just let us

rattle and nobody said, "We gotta cut

the time." It was just a really free

kind of thing. All of our performances

at the Fillmore were special. For us,

just because they had tape rolling in a

truck outside, it really didn't affect

us that much. We didn't play for the

tape, we played for the people.

Trucks: We played for roughly

seven straight hours with everything we

had. We played a three-hour set and then

came back out. The feeling from the

audience, not necessarily the volume,

but the feeling was just so overwhelming

that I just started crying. Then we got

into a jam, I think it was "Mountain

Jam" that lasted for four straight

hours. Nonstop. And when we finished,

there was no applause whatsoever. The

place was deathly quiet. Someone got up

and opened the doors, the sun came

pouring in, and you could see this whole

audience with a big shit-eating grin on

their face, nobody moving until finally

they got up and started quietly leaving

the place. I remember Duane walking in

front of me, dragging his guitar while I

was just sitting there completely burned,

and he said, "Damn, it's just like

leaving church." To this day, I meet

people who say they were there, and I

can tell if they were just by the look

in their eye.

Allman: Bill Graham's

introduction when he said, "We're going

to finish it off with the best of them

all — the Allman Brothers" — that is

something I'll always remember.

Trucks: I think Fillmore East

was the last truly honest, from-the-soul

record that we ever did. There's

absolutely nothing in there but us

playing music. Even by Eat a Peach,

a little bit of bullshit had started to

sneak its way in, and by Brothers &

Sisters, we were almost over the

edge of more bullshit than music. We

found ourselves in the position we swore

we'd never be in of being rock stars

playing bullshit rather than being

musicians playing music.

Allman: No one did it better in a

live setting than the Allman Brothers,

and Fillmore East is still the

proof, all these years later.

Betts: It was a great band, good

music. It's honest, I guess.

|

CORBIN REIFF: |