|

|

JESSE

GRESS: |

Twenty-two years after his passing, Duane

Allman remains the unsurpassed king of electric slide guitar.

Already steeped in the blues of Muddy, Wolf, Willie Dixon, B.B.

King, Clapton, and Beck, Duane became enamored with slide after

hearing the late Jesse Ed Davis perform Blind Willie McTell's

"Statesboro Blues" with Taj Mahal at an L.A. club. Using a glass

bottle for a slide, Duane also began emulating Little Walter,

Sonny Boy Williamson, and other blues harmonica players. In

time, even his non-slide playing took on characteristics of his

bottleneck style, as if both were becoming welded into one

voice.

Duane was

obviously a fast learner with an uncanny grasp of open-E

tuning, as heard on his records with the Allman Brothers Band

and soulful backing of Wilson Pickett, Aretha Franklin, King

Curtis, John Hammond, Boz Scaggs, Clarence Carter, and others.

Though he began playing bottleneck in standard tuning, Allman

preferred the advantages of open E, and he eventually

limited his standard-tuned slide excursions to songs like

"Dreams" and "Mountain Jam."

Early in

1970 the Brothers cut a studio version of "Statesboro Blues" in

the key of C, while the later live At The Fillmore

version was in D. A few months later, during the

recording of Idlewild South, Allman tracked more

cutting-edge, open-E-tuned electric slide on "Don't Keep

Me Wonderin' " and "One More Ride." Continuing his session work,

he began to hit his stride later that year during Eric Clapton's

Layla sessions. His bottleneck ranged from subdued to

incendiary on eight of these tracks, almost all of which are in

open E ("Layla" and "I Am Yours" are the exceptions).

The Layla outtake "Mean Old World," a dobro duet with

E.C., is perhaps Duane's only recording in the more rural open-G

tuning. Duane's next big project, the Brothers' At Fillmore

East, represents the pinnacle of bottleneck performance,

the book of electric slide.

Gear-wise, Duane favored Les Pauls, 50-watt Marshalls, and a

glass Coricidin bottle worn over his ring finger. While sliding,

he used his right-hand thumb, index, and middle fingers, which

served double duty damping unwanted strings. Duane also used his

left-hand middle and index fingers to damp behind the bottle.

Low frets and medium-high action were also helpful. For accuracy

like Duane's, align the tip of your ring finger directly over

the fret.

Guitarists commonly use bends, hammer-ons, pull-offs, and finger

slides to get from one note to the next. The slide imposes

limitations on these techniques but offers several alternatives.

In Ex. 1a both notes are fretted with the slide with no audible

glissando in between. Ex. 1b features a picked grace-note slide

into the second note, a motion performed with a single pick

attack in Ex. 1c. Think blues harp for the even gliss in Ex. 1d.

The grace-note slide preceding the first note of each previous

example adds even more smoky harmonica flavor.

|

|

The advantages of open-E tuning are increased string tension (for more sustain) and economy of motion. Raising the open fifth and fourth strings a whole-step and and the third string a half-step produces an open E chord (Ex. 2a), giving you, from low to high, the root, 5th, root, 3rd, 5th, and root. Since the root positions are on the 6th and 1st strings remain unaffected, it's not necessary to relearn notes when moving the chord shape around the fingerboard. Using the slide to barre all six strings, this chord voicing may be transposed to 11 other fret positions to accommodate chord changes or playing in different keys before recycling an octave higher (Ex. 2b). Open-E tuning also offers easy access to all three triad inversions, playable as chords or arpeggios. Ex. 2c demonstrates this while summarizing Duane's right-hand technique. For arpeggios, begin with the fingers resting on the strings as if you were about to play the entire chord, and then pluck each note individually.

|

|

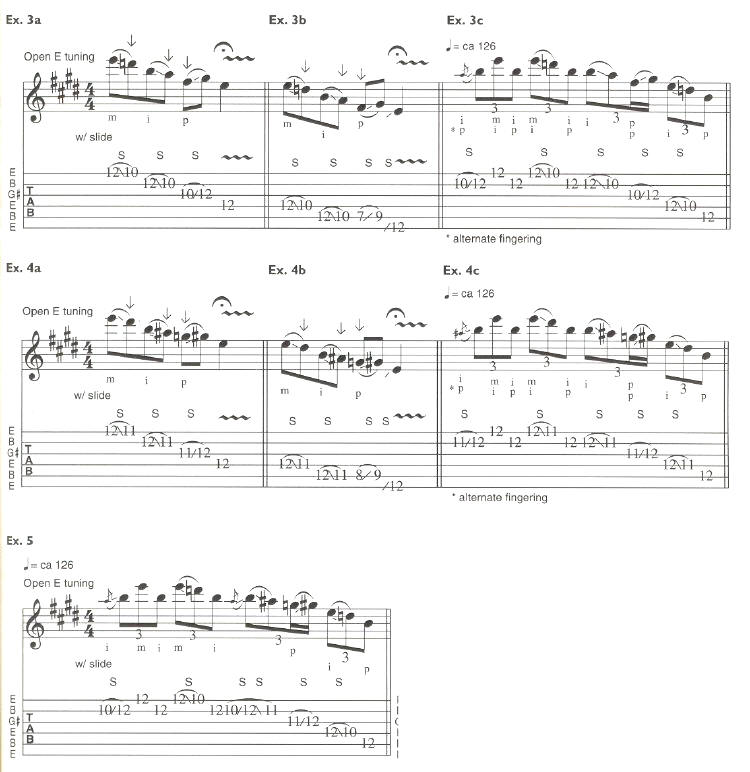

When it

came to spinning single-note lines (which comprised 99% of his

slide work), Duane preferred the urban "box" approach over more

traditional open-string stylings. The box shape is formed by the

addition of neighbor tones below the tonic chord position.

Examples 3a and 3b illustrate the lower neighbors (notated below

the downward arrow) a whole-step below each chord tone. These

lower neighbors (the lowered 7th, 4th, and 2nd/9th) are

incorporated in a typical Duane-style lick in Ex. 3c. Examples

4a and 4b show the chromatic half-step neighbors (the natural

7th, raised 4th/lowered 5th, and lowered 3rd), while Ex. 4c

adapts them to the previous lick. In Ex. 5 the same lick is

treated to a combination of whole-step and chromatic lower

neighbors.

Be sure to explore another important element of Duane's sound,

the world of sweet 'n' sour microtones present between neighbor

tones. Transpose these ideas over the entire fingerboard.

Remember, Duane played just as fluently in any key.

|

|

The next few examples cover some of the building blocks of Duane's style. Each motif stands on its own and may be developed in many ways, including repetition, rhythmic displacement, elongation, and retrograde. Ex. 6a features a four-note motif moving across adjacent string groups with whole-step lower neighbors. Ex. 6b shows what a difference a subtle change in phrasing can make. Examples 7a through 7d follow the same logic using a five-note motif. For some astonishing variations, try replacing the whole-step lower neighbors marked by asterisks with chromatic neighbors or in-between microtones.

|

|

Neighbors above the tonic chord include the 2nd/9th, 6th, and 4th. Duane used these sparingly, mostly as grace-note slides or for an occasional splash of pentatonic-major color. Instead, he'd extend the box by momentarily zipping up a major 3rd on the first or fourth strings, or by using the important minor-third spacing (only found between the 2nd and 3rd strings) to create a dominant 7th chord fragment three frets above the tonic. In E, sliding up three frets from the tonic's G♯ and B yields B and D♮, part of the E7 chord (Ex. 8a). Ex. 8b shows the whole-step and chromatic neighbor possibilities for both two-note structures.

|

|

Culled from medium-tempo shuffles, Examples 9a through 10b capture some of Duane's signature phrases. All have been transposed to E for mixin' and matchin'. Ex. 9a is very harmonica-like. Add even more sass by exploiting those microtones. Ex. 9b uses the implied 7th chord described above, and then outlines a descending box combining whole- and half-step lower neighbors. Ex. 9c's chromatically ascending minor thirds lead up to a signature major third jump up the first string before the descending box/octave-leap conclusion. A similar move in Ex. 10 navigates the IV-I change, as does Ex. 10b, a funky mid-register harp lick.

|

|

Transposed to the key of D, the blues harp outing in Ex. 11 covers the last four measures of a 12-bar blues. Duane's flawless intonation is evident as he zips off the fingerboard to the hypothetical 26th fret. Move it up a whole step (to E) for a real trip into the stratosphere.

|

|

When bottlenecking in standard tuning, Duane often wove adventurous linear excursions up and down the string in place of the blues-box approach, perhaps partially influenced by his interest in jazz greats Miles Davis and John Coltrane. Duane's melodic development is masterful in Ex. 12, taken from a videotaped performance of "Dreams." His two-bar call-and-response lines emphasize a 3/4 pulse, while the rhythm section lays down a 6/8 jazz waltz. Special thanks to brother Jas O. for supplying valuable reference material.

|

|